Cartoons to combat snakebite: the hunt for a popular cartoon character in Myanmar

Snakebite – a major public health concern

Snakebite, disregarded for so many years, is finally getting the attention that it deserves. Conservative assessments estimate that snakebite is responsible for up to 138,000 deaths each year, with many more left with permanent disability. An affliction of the rural poor across much of Asia, Myanmar is a country with a notably high incidence of approximately 116,000 per 100,000. It is an agricultural country with many communities that rely on farming for a living.

There remain many barriers in accessing anti-snake venom in a timely fashion. Many people continue to seek traditional treatment for snakebite, thereby delaying presentation to a health professional and can, in their own right, be responsible for considerable morbidity and mortality. Tourniquets are routinely applied to manage snakebite, however, and other methods such as tattooing, cutting, burning, attempting to suck the venom out and the use of herbal medicine are also commonplace in Myanmar.

During time spent talking to different healthcare professionals on my arrival in Yangon, many emphasised the importance of prevention in tackling snakebite. In 1994, posters were created to educate the public about how to prevent snakebite and what actions to take following a bite. There was also one depicting the venomous snakes in the country. These were not widely in use and in any case appeared to be in need of updating.

I asked a number of doctors and nurses for feedback on the existing posters and how they could be improved. Many areas for development were highlighted, but overwhelming positive feedback was given for the featured cartoon character, called "Tut Pi".

This hunter character is a figure that was recognised and loved by all. Cartoons remain popular in Myanmar, which experienced a late digital bloom, after censorship was abolished in 2012. Many people remain illiterate and hence the power of images to convey a message cannot be underestimated.

The Hunt for Tut Pi

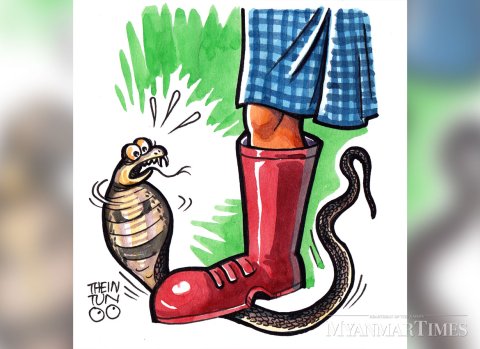

Given the positive feedback, I was determined to use Tut Pi to develop the new posters. Through writing articles for the Myanmar Times, I met with their cartoonist, Thein Tun Oo, in an attempt to find the creator of the elusive character. It became apparent that the creator, U Swe Min, had sadly passed away. Through more detective work, the knowledge that his wife was a resident on the outskirts on Yangon and was still publishing the cartoons gave hope that gaining agreement for Tut Pi to appear in the new snakebite cartoons could become reality.

Through the means of a Facebook post on a popular page for both expats and local Burmese, I was given an address. Not sure what I was expecting to find, I made my way to the designated location, a house in an urban area in the north of the city. Wrought iron gates blocked the view into the front of the house – but with the figure of Tut Pi engraved into them, I knew I had come to the right place! Fortune favours the determined; I was greeted by Daw Moh Moh San, the widow of U Swe Min, creator of Tut Pi.

With the help of a translator, I was able to express my desire to use Tut Pi to make new snakebite education posters; she kindly agreed to this proposition and gave me the copyright. Over the course of future meetings with Kyi Naing, the current cartoonist, we developed and refined the new cartoons. There were many stages during this process, with continual feedback from colleagues in the hospital, until we reached a final version that was acceptable.

Snakebite study in Myanmar

With the help of local colleagues, I conducted a retrospective study into snakebite. Data was collected about the patients admitted with snakebite in 2018 to Yangon General Hospital and provided some evidence as to the different methods currently used to treat snakebite in the community. This was utilised to choose the most relevant pictures to include in the new posters.

The snakebite prevention poster depicts Tut Pi doing different parts of his daily routine, highlighting features that can help prevent snakebite – for example, the use of a well-tucked in bednet can not only keep out mosquitoes, but also snakes that might enter the house at night.

The snakebite first aid poster emphasises the pressure-pad immobilisation technique, which was shown to be effective in Myanmar by Professor Tun Pe. The third poster using Tut Pi was completely new, focusing on detail on the different inappropriate methods used locally to treat snakebite. These pictures and text are accompanied with a red cross, whereas the first aid cartoons feature a green tick.

Updated posters of the venomous snakes of Myanmar include better quality images to aid snake identification, alongside some medically important information to help identify the snake responsible for envenomation by the clinical syndrome.

The text and pictures were also reviewed by Professor David Warrell, editor of Guidelines for the management of snakebites for the South East Asia region. Professor David Warrell kindly provided pictures of the venomous snakes of Myanmar and his support of the project throughout is gratefully acknowledged.

Spreading the word

The new posters were put up around Yangon General Hospital, including the emergency department, which sees the majority of patients admitted with snakebite.

The materials were also given to NGOs to use. Following submission to the Ministry of Health and Sport, the aim now is to field-test the posters with a view to using them across the country as part of a public health campaign.

Since their development, there has also been interest in using the cartoons as part of public health education in Tamil Nadu, India. Snakebite remains an area of significant need in Myanmar, and I hope to have the opportunity to return in the future, to build on and develop the work completed to date.

The future of snakebite in Myanmar

The cartoon character Tut Pi is the cornerstone to the success of the snakebite education resources in Myanmar. An understanding of the culture and the use of different forms of media are essential in developing resources to be used in public health education.

Particular importance should be placed on the use of pictures or images in places where rates of literacy remain low. There remains much work to be done to engage with rural and remote populations, if current attitudes and behaviours around snakebite are to change. This is time-consuming and labour intensive, but surely worth the endeavour.

A greater focus on prevention in public health efforts such as this to combat snakebite is vital, if we are to make significant steps towards halving disability from snakebite by 2030, as is stated in WHO’s snakebite roadmap, in not only Myanmar, but globally.