Dominance of highly resistant bacterial pathogens in post-caesarean surgical site infections in Uganda

I have a special interest in management of infectious diseases in pregnancy which led me to undertake the EADTM&H course.

I was excited to share the findings of my research on antibacterial resistance at the EARIP conference, which was a great platform to contribute to the growing knowledge on antibacterial resistance especially in Africa where this is increasingly becoming a threat.

Surgical site infections (SSIs) are some of the commonest complications of caesarean sections (C/S) worldwide. In resource-limited settings, post C/S SSI are often managed empirically using antibacterial containing third generation cephalosporins without prior culture and susceptibility data.

Data published by WHO in a global report on surveillance of antimicrobial resistance in 2014 indicated that resistance by E. coli, K.pneumoniae and S.aureus to commonly used antimicrobials exceeded 50% in most clinical settings.

How was the study conducted?

I carried out a cross-sectional study between December 2017 and April 2018 at Mulago National referral hospital Kampala, Uganda.

The study looked at the burden and mechanism of resistance to third generation cephalosporins among gram negative bacteria and methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) pathogens from post C/S SSIs

Wound swabs collected from 109 post C/S SSIs were cultured for pathogenic bacteria following standard microbiology procedures.

The Kirby-Bauer disc diffusion and PCR techniques were used for susceptibility testing. Data was analysed using SPSS-IBM Statistics v16.

The study results

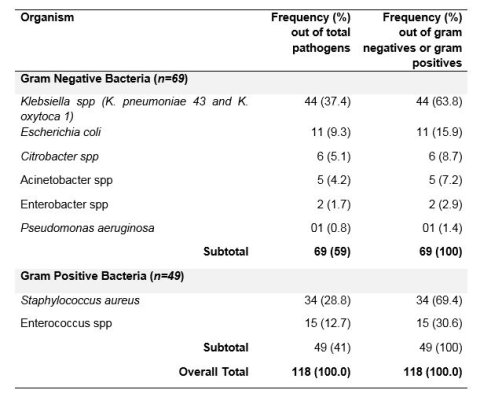

93 swabs (86%) turned culture positive with one or more pathogens giving 118 pathogens.

Gram negative bacteria (GNB) accounted for 69/118 (59%) pathogens while 49 gram positive bacteria (GPB) were detected as shown in the table.

Resistance among gram negative bacteria: All gram negative bacteria were 100% resistant to ampicillin but 100% sensitive to amikacin. Resistance to ceftriaxone was found in 98% of K. pneumoniae, 100% of E. coli, 83% of Citrobacter and 50 % of Enterobacter.

Other than Klebsiella pneumoniae and Acinetobacter species, the rest of the gram negative bacteria were 100% susceptible to carbapenems.

Overall the mechanism of resistance to third generation cephalosporins was explained by ESBL production in 91% of E. coli but only in 50% of Klebsiella species. All the E. coli pathogens were sensitive to carbapenems while 37.5% of the Klebsiella species showed additional resistance to carbapenems.

ESBL production as a mechanism of resistance has been called a “better problem” as these organisms are potentially treatable with a combination of a third generation cephalosporin and beta-lactamase inhibitor or with carbapenems.

But Carbapenem resistance is worrying because Carbapenem antibiotics have been used as the last resort salvage treatment for infections caused by multidrug resistance gram negative bacteria (MDR-GNB). Infections caused by gram negative bacteria with amp-C or carbapenemase resistance are extremely difficult to treat and may carry overall mortality of up to 50%.

Resistance among gram positive bacteria: All the gram positive bacteria isolates were susceptible to vancomycin or Linezolid. Among the 34 Staphylococcus aureus pathogens, 97% were resistant to penicillin and 91.2% were methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA).

Infections due to MRSA resistance can only be treated with other chemical classes of antimicrobials (not beta-lactams).

If they are local infections such as in our study participants, oral treatment with the modestly susceptible ciprofloxacin (50% susceptible) could be considered otherwise those with systemic infections require vancomycin which is expensive and out of reach for most patients in our setup.

Where do these results fall within the global burden of antibacterial resistance?

A 2017 WHO report reiterated the concern that the world is running out of antibiotics. The report found that the majority of drugs currently in the clinical pipeline did not represent new antibiotics but modifications of existing classes of antibiotics and as such only short-term solutions.

As stated in the report: “there is a serious lack of treatment options for multidrug- and extensively drug-resistant M. tuberculosis and gram-negative pathogens, including Acinetobacter and Enterobacteriaceae (such as Klebsiella and E. coli) which can cause severe and often deadly infections that pose a particular threat in hospitals and nursing homes.”

My findings of higher prevalence of MRSA among S. aureus, ESBL among E. coli and now emerging carbapenem resistance among K. pneumoniae are therefore not in isolation and calls for strengthening evidence-based prescriptions and ongoing resistance surveillance.

In addition, as the WHO recommends, new treatments alone will not be sufficient to combat the threat of antimicrobial resistance but ultimately improving infection prevention and control and promoting appropriate use of existing and future antibiotics will be the way to go to counter the threat of antibacterial resistance.

To further address the problem, the WHO and the Drugs for Neglected Diseases Initiative (DNDi) set up the Global Antibiotic Research and Development Partnership (known as GARDP) to increase research and funding for new antibiotics.

More funding in the area of antimicrobial resistance needed

I was honoured to present my findings and to win the award for best oral presentation during the EARIP meeting in Moshi, Tanzania.

At this meeting, I noted other studies being presented that had been done in African countries and clearly outlined similar findings of worsening anti-bacterial resistance in the region which calls for further commitment in terms of research funding into describing the scale of the problem and finding new antibiotics.

I aim to further evaluate the additional mechanisms of resistance by gram negative bacteria through PCR and hopefully influence drug prescription behavior in Sub-Saharan Africa.