It is the time to refocus on AMR

If you take a minute and stare far off into the haze on the horizon, past the personal, economic and political stories and consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic, past the league tables of testing, infections and deaths, and the stories around the international scramble to mobilise every aspect of our healthcare response towards the SARS-Cov-2 virus, you might just see something familiar.

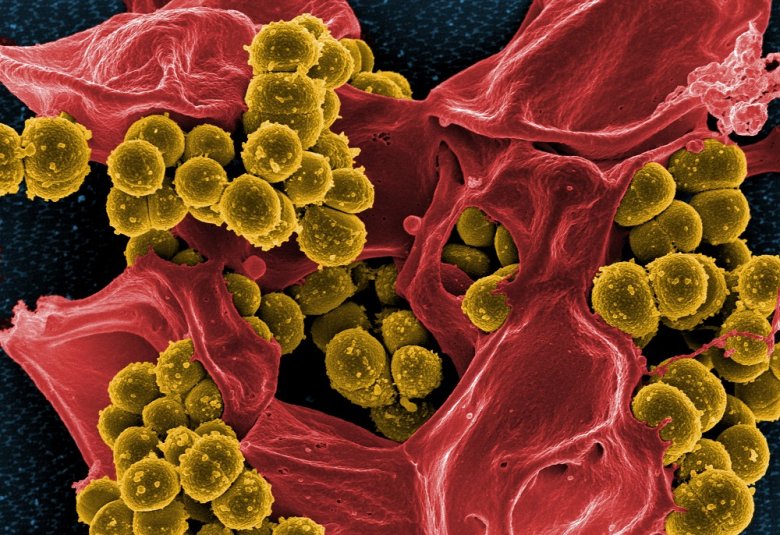

Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR) is still there, still increasing at an almost imperceptible rate. It is noticeable only to those who either work in related disciplines, are directly affected by it, or by those who want to know about it and seek it out. It is increasing just slowly enough to avoid the glaring scrutiny of the media in these times when there is so much else to focus upon.

AMR, like almost everything else in the world over the last 10 months has been thrust into the shadows of COVID-19. This is why the World Antimicrobial Awareness Week 2020 (WAAW 2020)is particularly important. Not only in raising awareness of AMR, but also in refocusing on a problem that is not going to fade into the distance and will only get worse if we take our eyes off it for a while.

A noticeable change this year is the use of the word Antimicrobial in place of Antibiotic within WAAW 2020. This change in focus, agreed by the tripartite organisations ; the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), the World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE) and the World Health Organization (WHO), expands the scope of the campaign to all antimicrobials. It is hoped that it will facilitate a more inclusive global response to AMR and further support One Health solutions.

AMR does not stand alone from COVID-19, indeed our response to the pandemic is likely to affect AMR in multiple ways. There has been an increase in the use of certain antibiotics within clinical settings, and the world is now awash with antiseptics and biocides for personal and homecare cleaning like never before. But if we look deeper, we can see that our behaviour has also changed. Health-seeking behaviour for example, particularly during peaks of infection and local and national lockdowns, have led to increasing virtual visits to the doctors resulting in changes in prescription patterns. Social distancing, both in hospitals and in societies, may lead to less transmission of pathogens between individuals. How these adaptations to COVID-19 will ultimately affect AMR remains to be seen, as it could be years before these changes manifest into clinical reports captured by GLASS, the World Health Organization’s Global Antimicrobial Resistance and Use Surveillance System. Any effect on AMR will depend on the longevity of change in our use of antimicrobials (and the subsequent selective landscape on microbes), so if COVID-19 can be rapidly controlled with a vaccine, it is possible that fewer long-term effects on AMR will be seen.

What COVID-19 has highlighted however, which is directly relevant to AMR, is the fragility of some healthcare systems. We have seen the devastation in hospitals that a single, easily transmissible, disease can bring with it and how little time it takes to reach the edge of healthcare capability in multiple countries. This in itself should be enough to galvanise a renewed and sustained focus on AMR because, unlike a single infectious agent, increasing levels of AMR mean we could have to deal with multiple, untreatable infections at the same time.

Another important aspect is pandemic fatigue. Increasingly individuals are feeling demotivated about following guidance, advice and rules implemented to protect themselves and others from COVID-19. This acceptance of a new norm and associated apathy is something we must work hard to avoid in terms of AMR, as an individual within society is an incredibly powerful agent of change, whether that be by appropriately advocating the use of antibiotics within a community, or by demanding a food retailer reports if antibiotics are used in the production of food they sell.

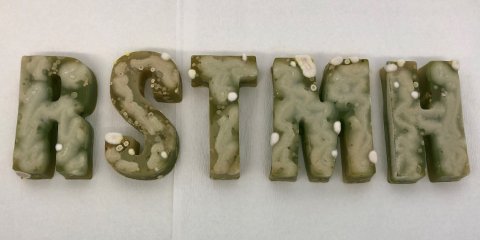

Finding novel solutions is difficult, as there are many already being worked on, however a renewed focus can also be reinvigorating. One thing we should do is to find out exactly what is happening at local levels. Implementation of One Health-based, locally-scaled AMR surveillance systems for bacteria and fungi would be exceptionally useful. It would help rapidly identify changes in resistance epidemiology before it manifests in clinical settings and would also be more accessible for individuals to understand what is going on within their community in terms of AMR. It would also serve as an early warning system when new resistances and unusual pathogens emerge. This later aspect is critical as we need to know the unknown. During COVID-19 we continue surveillance for the WHO priority pathogens and other usual suspects, but what of our reduced capacity to monitor the less well-known and emerging bacterial and fungal pathogens?

Being prepared to tackle the emergence of resistance in the next major pathogen is crucial, as being reactive against a microbiological foe has been devastatingly exposed this year as the least desirable way forward.