Monkeypox: the latest public health emergency of international concern

Professor Jimmy Whitworth, Emeritus Professor of International Public Health at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine and RSTMH Trustee, gives an overview of the monkeypox epidemic, including current cases, symptoms and the public health response.

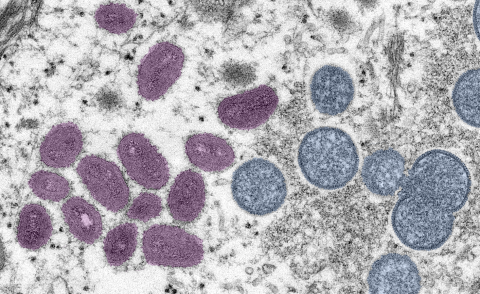

In less than three months since the first case in the UK, by 29th July 2022 there had been over 22,000 cases of monkeypox reported in 79 countries around the world. This is an extremely unusual epidemic as monkeypox naturally occurs in west and central Africa forests, mostly in people reporting close contact with small rodents or squirrels. It is caused by infection with the monkeypox virus, a close relative of the eradicated smallpox virus.

In endemic African countries therefore this is a zoonosis (an infection acquired from animals), and many millions of people are at risk of infection simply by living in a forested area. The endemic area seems to have expanded and numbers of reported cases have been increasing substantially since the 1970s, especially in Democratic Republic of Congo and Nigeria. This is probably at least partly due to falling levels of the immunity that was provided by routine smallpox vaccination which stopped in the 1980s after smallpox was eradicated.

Cases outside Africa have been reported occasionally in the past in people travelling from endemic countries while incubating the infection, apart from one outbreak in the USA associated with the importation of a consignment of infected pet animals. Human-to-human transmission outside Africa has been rare, probably due to prompt recognition of cases and stringent isolation measures.

The current epidemic

The current epidemic is therefore unprecedented. The most likely reason for this is that the virus has exploited a niche where it can flourish. Over 98% of the cases reported from numerous European and American countries have been in men who identified as gay, bisexual or other men having sex with men (GBMSM). Many of them had attended international festivals and venues and were part of an extensive sexual network. There have been a few confirmed cases in women and children. The mortality rate has been low with 10 deaths reported in 2022 so far, 5 of which were in non-endemic countries outside Africa. Transmission is known to occur through close contact: skin-to-skin, shared utensils or bedding or from respiratory droplets, and anyone in close contact with a case can become infected. Close contact associated with sex with multiple partners would be sufficient to drive the epidemic, although there are suggestions it may also be sexually transmitted through live virus present in semen.

Many patients in this outbreak have reported the classic symptoms of fever and lethargy, myalgia and headache, lymphadenopathy and the characteristic rash with blisters, pustules and scabs. But some cases have had only mild systemic illness and unusual rashes, sometimes just in oral or genital regions, accompanied at times with severe pain. It is possible that the virus has mutated to become more transmissible from person to person by thus is not yet certain.

Public health control

Public health control has been based on prompt case detection, isolation and treatment and tracing and supporting their contacts, together with extensive community engagement. Most cases can be managed at home, less than 10-15% have needed outpatient or inpatient hospital care. Vaccination with MVA-BN (Imvanex / Jynneos), a smallpox vaccine has been offered to contacts of confirmed cases, ideally within 4 days of exposure, and to high-risk individuals, including those living with HIV. The World Health Organisation (WHO) declared the monkeypox outbreak a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC), the highest level of alert, on 23rd July. Although the expert committee had not reached consensus on this, Dr Tedros Ghebreyesus, director general of WHO, stated: “We have an outbreak that has spread around the world rapidly, through new modes of transmission, about which we understand too little and which meets the criteria in the International Health Regulations.”

By declaring the outbreak a PHEIC, WHO will expect increased international co-ordination, strengthening the response, and raise awareness amongst health workers and the communities at risk. Work is needed to reduce stigma and discrimination, as in many countries GBMSM are marginalised and criminalised, and this may drive cases and transmission underground if patients are scared to present themselves. More research is needed urgently to better understand how the infection is transmitted from person to person, and also whether humans might infect animals leading to a reservoir of infection in animas outside Africa. We need to work to improve access to rapid diagnostic tests and measure the effectiveness of antiviral drugs and vaccines.

It would be unfortunate if declaring a PHEIC now sends a message that a disease that has been steadily increasing in Africa for decades is only declared an emergency when it affects rich countries in Europe and the America. What does this say about global health priorities? It is very important to seize this opportunity to increase capacity in west and central Africa for surveillance and response for monkeypox and other diseases of epidemic potential in the region. Supplies of monkeypox vaccines need to be expanded and distributed in an equitable fashion, to demonstrate global solidarity. We need to learn the lessons from the recent COVID-19 pandemic.

Topics in Infection

Emiritus Professor Jimmy Whitworth will be presenting on monkeypox at next month’s 47th Annual Topics in Infection meeting, taking place at The Great Hall, St Bartholomew’s Hospital, London, UK on 20 September 2022.

Check out the other topics and speakers at the one-day meeting and buy your ticket using the link below.