The road to zero leprosy: Insights from Malawi

For World Leprosy Day 2025 (26 January 2025), Nathan Singano, a public health researcher with a focus on neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) and an RSTMH/NIHR Early Career Grant 2023 awardee, wrote about his project on 'Beyond Eradication: Evaluating Leprosy Interventions and Knowledge in Malawi'.

Leprosy, a curable neglected tropical disease (NTD), has long afflicted humanity. While religious texts historically associated with leprosy were tempting to reference, I will instead focus on the scientific and public health aspects. What we know so far about leprosy is that it is caused by Mycobacterium leprae, a bacterium that primarily affects the skin, peripheral nerves, upper respiratory tract, and eyes. Early signs include discoloured skin patches and loss of sensation, along with nerve damage leading to muscle weakness. If these symptoms are not recognised early and the disease is left untreated, permanent disability, such as deformities in the hands, feet, and face can occur.

Leprosy persists because of a combination of biological, social, and structural factors. On the biological front, Mycobacterium leprae, the bacterium causing leprosy, has various clinical presentations and pathological characteristics that complicate its diagnosis and contribute to its persistence. With an incubation period ranging from months to years, the disease’s slow progression further challenges early detection.

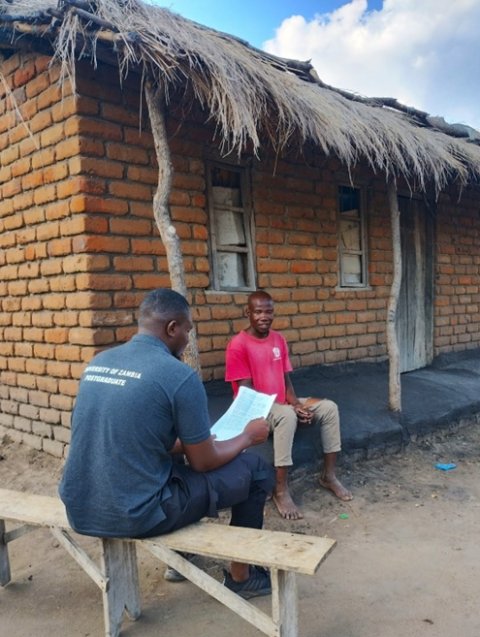

Socially, stigma and lack of knowledge perpetuate the cycle. I recently evaluated knowledge and leprosy control interventions among community members and healthcare workers (HCWs) in Malawi. I was primarily motivated by the resurgence of leprosy in Malawi despite national elimination in 1994. This study, funded by an RSTMH/NIHR Early Career Grant, revealed alarming gaps, with most participants unaware of leprosy causation, government interventions to control the disease and the persistent stigma within communities.

Structural barriers, such as limited healthcare access in remote areas, further hinder timely diagnosis and treatment. These factors, combined with high poverty and poor sanitation, create a conducive environment for leprosy to persist, especially in vulnerable populations. Low funding prioritization also limits the resources necessary for effective leprosy control programs.

Contrary to common misconceptions, leprosy is not highly contagious. It spreads through prolonged close contact with an untreated person, mainly via droplets from the nose and mouth. The disease’s low transmissibility means that most people will not contract it even if exposed, especially with a healthy immune system. While prevention largely involves education and awareness, single-dose rifampicin (SDR) as post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) is a game-changer in protecting close contacts. Surprisingly, in the same study, most participants were unaware of SDR-PEP. Interestingly, there was a significant willingness to adopt it if it was made accessible.

Prevention starts with awareness. Educating communities about leprosy can significantly reduce stigma. Early detection and treatment with multidrug therapy (MDT), provided free by the World Health Organization, effectively cure the disease and stop transmission. Strengthening health systems to ensure accessible diagnostic and treatment services in rural and underserved areas is also crucial.

As a researcher in Malawi, I have observed how leprosy is associated with social determinants of health. A particularly notable insight is the pivotal role played by health surveillance assistants (HSAs) in connecting communities with health facilities. These frontline workers, often the first point of contact in remote areas, are essential for identifying potential leprosy cases. However, their efforts are hindered by insufficient training and a lack of diagnostic tools. Empowering HSAs with the necessary skills and resources can transform leprosy control efforts in Malawi and other similar settings.

Achieving zero leprosy requires a comprehensive approach. Combating stigma through culturally sensitive campaigns will empower communities with accurate information. Training frontline workers, especially HSAs, is essential to ensure early recognition of leprosy symptoms and timely referrals. Improving accessibility through mobile clinics and decentralizing diagnosis to health centres can enhance care, particularly in remote areas. Promoting research focused on social determinants of health, drug resistance, and innovative diagnostic tools is vital to uncovering barriers to leprosy elimination. Collaborating with local and international organizations will help implement community-driven interventions and secure necessary resources. Addressing these interconnected strategies will drive progress toward eradicating leprosy, particularly in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), where the disease remains a significant public health concern.