International Snakebite Awareness Day 2021: research, stories, data and articles

On 19 September, we mark the fourth International Snakebite Awareness Day.

It is an occasion to remember that 7,400 people every day are bitten by snakes, and 220–380 men, women and children die as a result. This adds up to around 2.7 million cases of envenoming, and between 81,000 and 138,000 deaths a year, the huge majority being in poor communities in low- and middle-income countries.

It is also a time to mark progress – despite the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic – and to recognise the passion and dedication of people working as public health and medical professionals, veterinarians and researchers to mitigate the impact of snakebite envenoming and the disability, loss of income and loss of life and income it can causes.

In addition, RSTMH can share our success in ensuring snakebite does not remain the most neglected of the neglected tropical diseases.

Small grants funded by Wellcome on snakebite envenoming research

We are thrilled to announce more awardees of our 2021 Small Grants Programme.

Wellcome Trust, as part of our ongoing longer-term partnership, is funding ten awards on snakebite envenoming research in low- and middle-income countries.

Of the awards, Dr Diogo Martins, Snakebite Lead at Wellcome Trust, said:

“We were very pleased with the number and quality of snakebite applications. The final selection was not an easy one, but one that we at Wellcome are immensely proud of.

“We trust that these 10 new grantees will add their voice, knowledge and ideas to a vibrant and diverse group of early career researchers in Snakebites from all around the world. We hope everyone will join us in celebrating and supporting this new cohort!”

Snakebite stories

We also asked members of the global snakebite community to tell us why they have dedicated their lives and careers to tackling snakebite.

Read more snakebite stories on the International Snakebite Awareness Day website

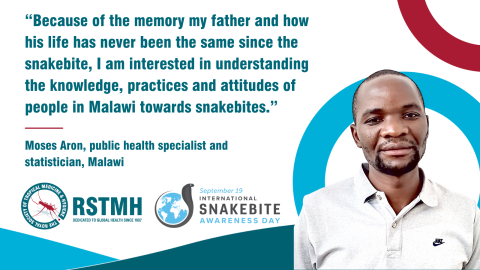

Moses Aron – a public health specialist and statistician in Malawi – recalls the day his father was bitten by a snake:

“We woke up early to work on the farm… after 30 minutes my father screamed: ‘something has bitten my foot’. The leg started swelling and I was terrified. We did not have money to transport him to the health facility. We had to sell goats to find transport. The wound took over eight months to heal and this affected our farm; the harvest in 2003 was not enough and we were struck by hunger.

“I was motivated to work hard at school and work in healthcare. Because of the memory of my father and how his life has never been the same since the snakebite, I am interested in understanding the knowledge, practices and attitudes of people in Malawi towards snakebites.”

Lack of data on snakebite

Demsy Audu, a PhD Candidate in Medical Sociology from the Federal University of Lafia, in Nigeria and a 2020 RSTMH small grant winner had a similar story:

“My uncle was bitten by a snake in 2015. We had to travel for more than 110 kilometres to a hospital specialising in snakebite. He died in the hospital after four days. We were still forced to pay all the bills accumulated for the number of days my uncle was admitted.

"Like my uncle, almost all rural dwellers and subsistent farmers in Nigeria are faced with snakebite issues. Despite this, data on morbidity and mortality remain scarce and in most cases absent.

"As a result, I have dedicated myself to helping to identify treatment pathways, since the Nigerian government has shown little or no attention to victims of snakebites as many bites are either treated through the use of herbs or go untreated.”

Traditional healers and peaceful co-existence

As well as focusing on traumatic personal experiences, some shared stories of empathy with the snakes themselves.

Mawuli Leslie Aglanu, a PhD student and research fellow in global health in Ghana, said:

“It is time to engage traditional healers to support the mainstream healthcare system in order to promote early referrals of snakebite patients. This will save more lives and also minimise the development of long-term physical and psychosocial disabilities following snakebites.

“It is time to debunk myths about snakes, especially in rural communities where human-snake conflict is prevalent. Snakes are not our enemies, rather we need to learn to cohabit by preserving their habitat while taking precautions to avoid bites.

Peris Njoki, a veterinary epidemiologist, agreed:

“My snakebite research is mainly to establish whether peaceful co-existence between snakes and human is possible. During my research work on snakebite risk factors in Baringo county [Kenya], I was also able to learn the 'goodness' of snakes during a focus group discussion.”

Antivenom and new therapies needed

It was also clear from the stories we collected that antivenom supply is an issue and more research is needed to develop new therapies.

Dr Robert Rono, is a medical doctor in Kenya who also holds a MSc in Field Epidemiology:

“I came across snakebite in my practice as a clinician in Baringo County Kenya and was intrigued that such a serious public health had been neglected. Antivenom supply was erratic at best and clinicians did not have confidence in administering antivenom. The burden was unknown and therefore the health managers could not forecast and plan for commodities.”

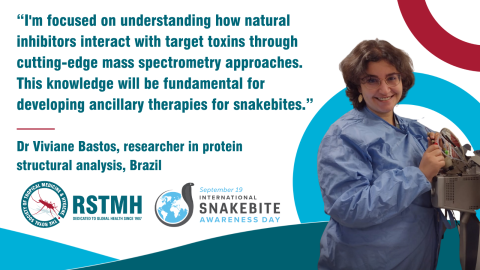

Dr Viviane Bastos, a researcher in protein structural analysis in Brazil, said:

“I am focused on understanding how [these] natural inhibitors interact with [their] target toxins through cutting-edge mass spectrometry approaches. This knowledge will be fundamental for developing ancillary therapies for snakebites. Knowing that my research can one day help ease the suffering of so many victims is what motivates me to keep going forward.”

WHO snakebite data and information platform

This week also saw the launch of WHO’s Snakebite Information and Data Platform to engage and empower communities. The platform will contribute to WHO’s strategy to reduce deaths and disabilities from snakebite by 50% by 2030.

Indeed, the new open access platform is a one-stop shop and central space for collaboration and data sharing for a range of stakeholders, including industry, NGOs and the general public. It brings together technology with data science and geography, using state of the art software and GIS to do.

The goal is to inform the public and public health specialists as to the location of antivenom and antivenom stockpiles, to identify vulnerable populations, empower communities to locate antivenom facilities, as well as learn about the ecology and epidemiology of snakes and snakebite.

The public is encouraged to get involved by contributing photos of snakes they encounter in the hope that the platform will marry citizen science with GIS in other WHO programmes and other partners’ work.

Journal mini-series on snakebite envenoming

Finally, we’re pleased to share a themed section in the September issue of Transactions, which is fully accessible to all and looks at envenoming issues in Sudan, Sri Lanka, Kuwait and Brazil.

Follow International Snakebite Awareness Day on social media through the hashtag #SnakebiteDay21.