Australia in the time of COVID-19

Dr Aaskov retired as Professor of Virology and Immunology at the Queensland University of Technology in Brisbane Australia in November 2019. Previously, he was also Director of a WHO Collaborating Centre for Arbovirus Reference and Research and is on the Register of Experts for the International Health Regulations. He is the RSTMH Country Ambassador for Australia.

Beginning on 23 January, 2020, passengers on flights from Wuhan, China, were screened by biosecurity officials on arrival in Australia, given an information sheet and asked to seek medical attention if they had a fever or suspected they have COVID19. The first cases of a SARS-CoV-2 infection in Australia were reported on 25 January in a Chinese citizen who arrived from Guangzhou on 19 January and in three other patients returning from Wuhan. In the beginning of February, the Australian government banned all travellers from China who had not spent at least 14 days in a country outside China (and not reporting cases of COVID 19 infection). By 28 January, the Doherty Institute in Melbourne had made the first isolate of COVID 19 from a patient outside China.

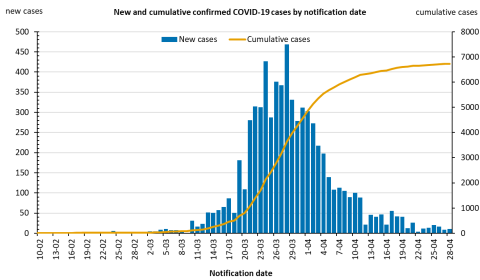

When the sequence for the whole genome of COVID 19 became available through WHO/GSAID, the Doherty Institute was able to modify their seasonal beta-coronavirus real time RT-PCR to detect this new virus. Subsequently, laboratories throughout Australia have used a mixture of approved, commercial RT-PCR assays and in-house ones to detect infection with this virus. By 28 April, Australia had performed 536,000 tests for COVID 19 infection (21,000 tests/million population), diagnosed 6,738 cases (264/million population) and recorded 88 deaths (3/million population).

Co-ordinating a response to any major health issue in Australia is a challenge because, while quarantine is the responsibility of the national government, health is a state issue. The disconnect is more of an issue at a political level than at an operational one, where there has been long standing co-operation and co-ordination between state and federal health officials. On 27 February, the Prime Minister announced that he was activating the Australian Health Sector Emergency Response Plan for Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19) and on 13 March, a National Cabinet, consisting of the premiers and chief ministers of the Australian states and territories was created, the first such cabinet since World War II. The cabinet meets weekly by video link and is advised by health ministers and an extensive panel of specialist advisors. While this has not resulted in uniform responses by the state governments (e.g. in relation to closing schools), there has been a lot of common action. Messaging from the government and from senior health officers has come from a very limited number of people who appear regularly on television. As might have been anticipated, there has been a certain amount of “white noise” from a small number of journalists and from individuals who have not been invited to advise the government but this does not appear to have diverted or diluted the core messaging.

Various forms of quarantine have been the first line response and Australia’s isolation, the relative independence of the states and the scattered population centres have aided this. All international arrivals, most of whom have been Australians returning home, are quarantined for fourteen days, at government expense, in hotels where there is twenty four hour surveillance of common areas to ensure no one absconds (one person who was sneaking out through an unalarmed fire escape at night to see his girlfriend has been heavily fined and threatened with jail). Many states restrict all but essential travel into the state and require 14 days quarantine for those who cross state boundaries. Within states, individuals are advised not to travel more than 50 km for non-essential travel and offenders have been fined for breaching this requirement. Those over 70 years of age have been asked not to leave home for anything other than critical travel. At a micro level, person to person spread had been restricted by social distancing of 1.5 to 2 metres between individuals. A consequence of these restrictions has been large numbers of people working from home and the closing of many commercial enterprises e.g. cafés, restaurants, shops and other retail outlets. There is a strong focus on hand sanitisation in those commercial enterprises still operating with unlimited alcohol-based hand sanitiser and disposable hand wipes available at the entry and exit to these premises.

More than 300 cases of coronavirus infection and 19 deaths have been linked to cruise ships docking in Australia and the circumstances surrounding the disembarkation of passengers from one ship is the subject of an ongoing criminal enquiry.

The restrictions on day to day activity imposed in response to the COVID 19 outbreak have led to some panic buying and shortages, some predictable and some not e.g. flour, pasta, tinned tomatoes, toilet paper, seeds to grow vegetables, pesticides for use in the garden and chicken manure (a popular organic form of fertiliser).

It remains to be seen, as Australia goes into winter, whether the anti-COVID-19 measures have any effect on the number of infections with influenza and measles viruses.