River blindness: A personal view

River Blindness (onchocerciasis) is a parasitic disease transmitted by the black fly. Unlike many other NTDs, it is not related to access to water and sanitation but simply to living close to a river where the flies breed.

Treatments used to be problematic – although there was Diethylcarbamazine (DEC) which killed the microfilaria (larval stage), it caused severe reactions.

Often the reaction was so severe that the patient’s vision could be compromised or lost completely so the treatment would have had to be stopped.

Mectizan

If I was a fisherman and saw small fish swimming in a clear stream or sticking to a rock, I may look at it in wonder. But looking in the eye with a slit lamp and seeing the microfilaria swimming in the aqueous humour or sticking to the cornea in the anterior segment of the eye heralds a serious outcome for the patient. While working in the DRC I used to go around my health zone (district) by motorbike.

One boatman, who lived near a breeding site and used to ferry me across the river in his dugout canoe, was treated with DEC and came to the hospital a couple of days later, having lost his vision completely. With the donation of Mectizan (ivermectin) in 1987, this all changed.

With community-directed treatment with invermectin (CDTI), the microfilaria gradually cleared from the eye, sometimes over a few weeks. There was no inflammation and the vision did not deteriorate further even if it could not be restored.

CAR in the 1990s

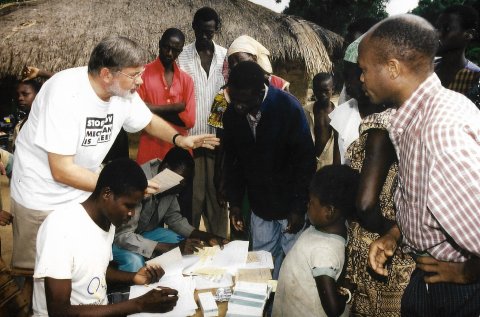

Working in the Central African Republic in the 1990s we lived close to the Ouham river and so we were exposed and got onchocerciasis.

Shortly after arriving, I went on an unscheduled visit to villages along the Ouham river one afternoon, mainly to recruit eye patients for cataract surgery as we had set up a new eye clinic. In the space of 3 hours I saw 34 people totally blind and I could not do anything for any of them.

I was saddened, but very much inspired and motivated to do something about this situation. With ivermectin we should be able to protect the younger population from similar suffering where, in some villages, 50% of the adult population suffered severe visual impairment or blindness.

MSD

While preparing a film to commemorate 25 years of the Mectizan donation by MSD (known as Merck & Co Inc. in the USA and Canada), we visited Bossangoa where I used to work in the Central African Republic. In a village near the town, a blind man called Michel came to chat with me.

He told me that he recognised my voice and in 1994 he had come to see me at the eye clinic because of his loss of vision. I could do nothing for his sight, so I referred him to the rehabilitation unit in the town.

As a young man, all his hopes of further education and a career were dashed and he came back to live in his uncle’s village, where he had stayed ever since. He told us that no one else in the village had gone blind, despite the interrupted annual treatment schedule due to civil war.

A proven principle

This personal reflection, and the impact of onchocerciasis on this one person’s life really instils that we must change the cycle of disease and poverty permanently, both for the individual and the community.

The principle has been proven in the Americas, where four countries have been verified free of river blindness by WHO, and in Africa where transmission of the disease has been eliminated in various foci - although no country has been verified free of the disease yet.

New cases of blindness are rare, except in areas with constant conflict e.g. in areas of DRC and South Sudan, but even here progress is being made.

I have concentrated on blindness, but we must not forget the similar impact of other manifestations of the disease, such as skin disease and epilepsy.

The social consequences of these manifestations can be equally as devastating as blindness. As we look to the future, we have no real hygiene strategy and no implementable lifestyle changes that will mitigate the disease in endemic areas.

If treatment stops before elimination of transmission is achieved, the disease will come back. We therefore must continue with Mectizan distribution, and the possible control of the vector, until elimination is indeed achieved.