Light out of Deep Darkness: Trachoma in Egypt

Ghana and Nepal are the latest countries to confirm that they have eliminated trachoma; this is indeed testimony to the dedication and efforts exerted by the international community over many years to ensure that this debilitating and highly infectious disease is consigned to history.

With this increasing success, it is perhaps salutary to reflect on the warriors from a previous era who fought the plague of ophthalmia and, in particular, the inspirational achievements of Arthur Ferguson MacCallan which I have recorded in the second edition of Light out of Deep Darkness.

As Arthur’s grandson, I am honoured to tell his story, bringing it to life through original letters, clinical reports recently discovered, colourful anecdotes and over 160 photographs.

Background

In 1903, Arthur (1872-1955) accepted a position in Egypt to establish the country’s first travelling ophthalmic hospital (TOH), funded by the British philanthropist Sir Ernest Cassel.

Cassel had been shocked by the extent of ophthalmia among the workforce constructing the first Aswan Dam (1892-1902) and established a Trust to “teach the principles of ophthalmic surgery to Egyptian surgeons” to ameliorate the suffering among the local population.

Estimates at that time suggested that 90% of the population of Egypt (of some 10 million people) suffered from ophthalmia, of which between 7% to 10% were blind in one or both eyes. Unfortunately, there were only four, badly equipped, hospitals treating few patients.

The ophthalmic campaign in Egypt

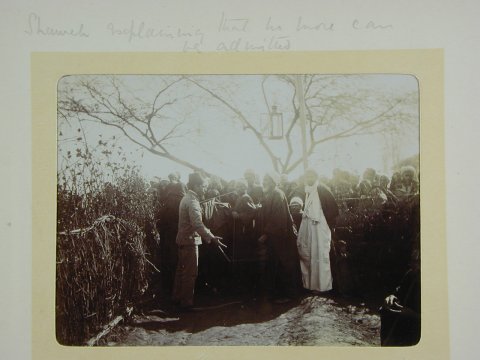

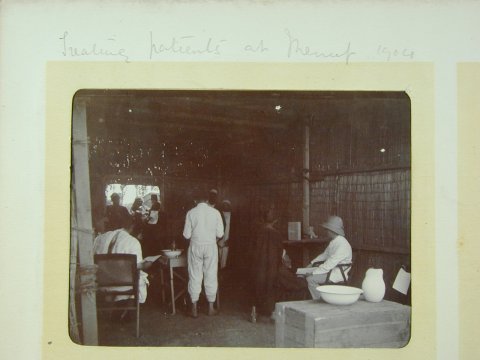

The first TOH, consisting of some 12 tents, was established at Menouf and opened in January 1904. Initially, there was reluctance by the local population to attend but this rapidly changed when the results of his operations became apparent.

Patients could literally “see” the benefits of Arthur’s work; demand for treatment became overwhelming as patients flocked to the camp (pictured left). In his early days, Arthur had to have police escort to control the over-enthusiastic crowd fighting for his attention!

During the first three months, he treated 6,157 patients and performed 615 operations, treating both men and women with equal consideration. Working conditions were harsh with the heat, sand, flies, lice and “mosquitoes as big as sparrows, very bony and strong”.

This combination of work and the environment put great strain on Arthur personally and he admitted that “the work is now very onerous” and “I don’t know how long I shall be able to stand this sort of life”.

Nevertheless, he persevered, recognising the overwhelming need by the population for ophthalmic treatment. Indeed, so successful were the results from the first TOH that, in 1904, Cassel provided the funds for a second one, initially established at Fayoum.

These TOHs were versatile. Generally, they spent six months at one location and then relocated to where essential ophthalmic treatment was also required. This versatility also proved extremely effective during the Ankylostomiasis (hookworm) campaign (1913) and during World War I, when they were converted to military hospitals treating casualties from the campaigns at the Suez Canal, Gallipoli and Salonica.

However, TOHs themselves were not a long-term solution and, given the high incidence of ophthalmia, Arthur devised a more robust and permanent solution to “create a stable central ophthalmic administration with the best possible clinical and scientific teaching adjuncts”, along with establishing a permanent ophthalmic hospital in each of Egypt’s 14 provinces. The first of these was opened in Tanta in 1908, funded by the government.

Over the following years, Arthur worked tirelessly to achieve his self-imposed goals. By the time he departed in 1923, there were 23 ophthalmic hospital units, including five TOHs, attending to 1.5 million patient visits and performing 76,000 operations, with a further two hospitals planned. He also trained some 100 surgeons to resource the expanding hospital network.

Lord Cromer (British Consul General, Egypt 1883-1907) made an insightful observation when he wrote to Arthur that “I regard the campaign against ophthalmia as one of the most important and useful works undertaken in Egypt.”

Ophthalmic research

Arthur is probably best known among the international ophthalmic profession for his research into and “classification of the stages of trachoma”. He analysed trachoma by identifying its component parts in a structured manner which enabled patients’ symptoms to be more readily identified and thus more readily treatable.

Arthur’s approach was to “convert the human suffering from trachoma into a concrete scientific and administrative problem”.

As early as 1905, he was using his classification internally; this was further developed in his books “Trachoma and its Complications in Egypt” (1913) and “Trachoma” (1936). In 1952, the WHO adopted “MacCallan’s Classification” as its then standard.

To support his research work, Arthur established the first ophthalmic laboratory in Assiut in 1913. Later Arthur founded the Giza Memorial Ophthalmic Laboratory, for research and pathological examinations.

This was opened in 1925, after his departure but he considered it to be “the coping stone of my work”. The laboratory is now known as the Giza Memorial Institute for Ophthalmic Research (MIOR) and continues to play a pivotal role in ophthalmic care today.

In 1931, Arthur’s work was recognised for his ophthalmic work with a commemorative bust being unveiled at Giza. This was a significant and rare honour for the Egyptians to bestow, particularly to a foreigner. Only two such commemorative busts were dedicated in that era, the other one was to Saad Zaghlul Pasha, the leader of the Egyptian independence movement.

Hygiene education to prevent trachoma

Arthur recognised the key drivers in the fight to prevent and eliminate ophthalmia; he was effectively using what is now known today as the WHO “SAFE” strategy but in a less structured manner.

He performed Surgery, insisted on Facial cleanliness and hygiene and was cognisant on the Environmental improvements required, particularly in the home and in the local community, to minimise the spread of disease. Unfortunately, this was the era before antibiotics.

With regard to hygiene and facial cleanliness, Arthur believed that if children could be educated in these disciplines from an early age, with particular emphasis on clean hands, faces and towels, then this could help reduce the transmission of the disease between people, both at school and in the home environment.

Indeed, one of his first initiatives was in 1903, when he visited the local school at Menouf to examine the pupils’ eyes.

“Perhaps the most important work carried out was the institution of ophthalmic treatment in all Government Primary Schools throughout Egypt.”

Arthur Ferguson MacCallan

Author’s reflections

Arthur always wanted to write a book of his time in Egypt; unfortunately, this never happened. So I have taken up this mantle and tried to capture his experiences through his letters home, clinical reports recently discovered and his photographs of that era.

Potentially, the first TOH was a high-risk experiment and could have easily been spurned by the local population. It was due to Arthur’s personal qualities, including perseverance, empathy with his patients and skill as an ophthalmic surgeon, that led to the success of the TOH at Menouf.

The pent-up demand for ophthalmic treatment grew rapidly thereafter. Arthur became his own ambassador in promoting and ensuring the implementation of his plans for the ophthalmic infrastructure which included persuading both government and local notables to provide the required funding.

Arthur’s legacy may be found in the many hospitals, established by him, which remain operational in Egypt today. For example, Fayoum has recently celebrated its 100th anniversary.

The MIOR at Giza also continues to play a pivotal role in ophthalmic care, with Arthur’s bust displayed inside. Furthermore, whilst the MacCallan Classification might have been overtaken by advances in medicine and science, it is still recognised today as a major contribution in the fight against trachoma.

Arthur’s pioneering spirit continues to resonate with the ophthalmic profession, as may be evidenced by the recent recognition of his accomplishments by the International Coalition for Trachoma Control (The ICTC MacCallan Medal) in 2014 and, for his services with military hospitals, the Moorfields Eye Hospital Commemorative World War I History Board, also 2014.

These are fitting tributes recognising that Arthur’s humanitarian campaign for the relief of suffering is still an inspiration to today’s profession as they continue their increasingly successful fight to eliminate trachoma.

Light out of Deep Darkness, a biography of Arthur Ferguson MacCallan, the trachoma pioneer – Second edition is published by The Choir Press, 2018 and is available from Amazon UK.